My maternal grandfather, James Bohaty, was the foreman in the press room that printed Lakeside Press’s Four American Books in 1930. I am grateful that I have been able to acquire them all.

My maternal grandfather, James Bohaty, was the foreman in the press room that printed Lakeside Press’s Four American Books in 1930. I am grateful that I have been able to acquire them all.

James Bohaty (1892-1984) worked at R. R. Donnelley and Sons in Chicago for 46 years, from before he joined its first apprenticeship class in 1908 until he retired 46 years later. On at least three different occasions the company’s in-house publications carried articles about him: as a press room foreman in 1923; upon his retirement in 1954; and in a 1983 four-page article that was one in a series celebrating Donnelley Pioneers. That third article is entitled, James Bohaty: Dean of the Letterpress, and includes several wonderful pictures (he is the man on the left in this picture). The articles praise his excellent work, his unfailing attention to detail, and his loyalty to the company. A loving husband, father, and grandfather, he was just as committed to excellence and attentive to detail in his personal life.

In the late 1920s Donnelley’s corporate leaders determined to publish four books that would represent the best in modern book design and production. These four books, to be published by Donnelley’s Lakeside Press, were to demonstrate that American ingenuity and artistry could mass produce books on a par with anything the best European craftsmen could produce using more traditional methods They chose four works and selected an artist to illustrate and design each book. Quoting the 1983 article, “(Donnelley’s executives) wanted to print, in limited editions, classic works by American authors. To that end, they called together the best illustrators, designers, typographers, printers and binders to meet the challenge: Produce the finest books ever done in America. Jim Bohaty’s pressroom was chosen to do the presswork.” One thousand copies of each book would eventually be published.

In the late 1920s Donnelley’s corporate leaders determined to publish four books that would represent the best in modern book design and production. These four books, to be published by Donnelley’s Lakeside Press, were to demonstrate that American ingenuity and artistry could mass produce books on a par with anything the best European craftsmen could produce using more traditional methods They chose four works and selected an artist to illustrate and design each book. Quoting the 1983 article, “(Donnelley’s executives) wanted to print, in limited editions, classic works by American authors. To that end, they called together the best illustrators, designers, typographers, printers and binders to meet the challenge: Produce the finest books ever done in America. Jim Bohaty’s pressroom was chosen to do the presswork.” One thousand copies of each book would eventually be published.

In addition to Four American Books my grandfather supervised the printing of some of The Lakeside Classics and of the volumes produced by Donnelley’s Holiday Press. I remember him talking with pride about printing the likes of Time and Life magazines, the World Book Encyclopedia, and even the massive Chicago telephone book and the Sears catalogue. Donnelley’s was one of the largest printers in the world at the time.

I recall some of the books on the shelves my grandparents’ living room as I was growing up. Through the decades I often scanned the shelves of rare book stores when searching for just one of the four. I never found any. But upon my mother’s death in I received her copy of Walden.

In 2017 the Cleveland Museum of Art offered an exciting exhibition of the art and culture of the the 1920s – The Jazz Age. Toward the end of our visit I remembered the Four American Books, which are products of that time, and decided to try to find the three I did not have.

Here are Lakeside Press’s Four American Books, with a few pictures of each.

Moby Dick, or the Whale, by Herman Melville; illustrated by Rockwell Kent:

Tales, by Edgar Allan Poe; illustrated by W. A. Dwiggins:

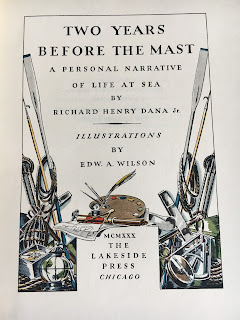

Two Years Before the Mast-A Personal Narrative of Life at Sea, by Richard Henry Dana, Jr; illustrated by Edwin A. Wilson:

Walden, or Life in the Woods, by Henry David Thoreau; illustrated by Rudolph Ruzicka:

I found Moby Dick first, and not far away. I had heard of Zubal Books on Cleveland’s near West Side. I called, and was told that they had a very fine copy of Moby Dick at what my online searches told me was a fair price. We went to see it the next day. As promised, it is beautiful, likely hardly ever opened, and in its original aluminum slip case. The following day we returned to Zubal Books and purchased it.

In short order I was able to purchase Two Years Before the Mast from a dealer inGloucester City, New Jersey, and Poe’s Tales from a dealer in Mount Desert, Maine.

Whether the Four American Books realize the goal of being (at least until 1930) “the finest books ever done in America” is of course debatable. There can be little doubt that if any of them deserves that title it is Rockwell Kent’s three-volume edition of Moby Dick. It is the most dramatic of them. Its massive volumes are bound in black with silver printing. Its jet-black ink drawings practically leap off the pages. Grandpa Bohaty liked to tell us how difficult it was to get the large expanses of black printer’s ink evenly spread on the paper. The market value of the original Moby Dick is significantly greater than the market value of the other three books combined.

A small one-volume “trade edition” of Melville’s classic was soon produced to be a Book-of-the-Month Club selection. Many, if not all of the original drawings are in it, but they lack the intensity of the originals. Fortunately, my mother’s older sister gave me her copy of the trade edition, which Kent had signed “for James Bohaty.”

Walden is often considered the best of the remaining three. Rudolf Ruzicka was a well-known illustrator and artist (and Czech, like my grandfather), and his highly-detailed woodcuts reflect the intensely personal nature of Thoreau’s thoughts. Inside the front cover of our copy of Walden Grandpa attached a note to him from Ruzicka expressing deep appreciation for the press work. It refers him a small engraving of a Hungarian town and inscribed “to James Bohaty.” It hangs in our home.

Poe’s Tales’ illustrations are dark and dramatic, befitting the horror conveyed in those stories. The intricate design of the decorations scattered throughout add a sense of the twists and turns of the Tales themselves.

To some Wilson’s work in Two Years is the most problematical. The colorful paintings seem to reflect more the style of 1920s print advertising than of early 19th-century sea-farers. But it is the only one of the books the uses color at all, and its cover is very striking.

I cannot judge the books beyond what I’ve written, and I do not know enough about the actual printing process, either now or nearly 100 years ago, to judge the quality of the print work. I do know they are all beautiful to my eyes, and I like to think that Grandpa Bohaty may well have held their pages as his keen eye made sure that they were just exactly as they were meant to be.

——————————-

Additional information about these books is available in Claire Badaracco’s American Culture and the Marketplace: R. R. Donnelley’s Four American Books Campaign, 1926-1930. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1992.